EMNLP 2018 Thoughts and Notes

10 Nov 2018This year’s EMNLP was bigger than any ACL conference ever before. With around 2500 attendees, a couple of hundred talks, and a few hundred posters, it was unthinkable to try and keep track of everything. Nevertheless, in this day-after-the-conference blog, bubbling over with ideas, we will do just that. Starting from the first workshop and concluding with Johan Bos’ Moment of Meaning, we will attempt to offer a convincing account of what happened in Brussels and what it meant for the future of NLP.

WNUT 2018

Using Wikipedia edits in low resource grammatical error correction

This paper builds a grammatical error correction (GEC) system for German. The authors combine two previously available German learner corpora: Falko and MERLIN to form the new Falko-MERLIN GEC corpus which contain ~24k sentences and their corrections. Next, they use the German Wikipedia edits to create a noisy, but bigger dataset. The ERRANT tool is used to filter this data by using the Falko-MERLIN corpus as the gold standard. A part of the Falko-MERLIN corpus is set aside as development and test sets and the rest is combined with Wikipedia data to train a convolutional seq2seq network to correct grammatical errors. The results show that incorporating the noisy Wikipedia data increases the accuracy of corrections. Including only the filtered part of Wikipedia increases it a bit more. —

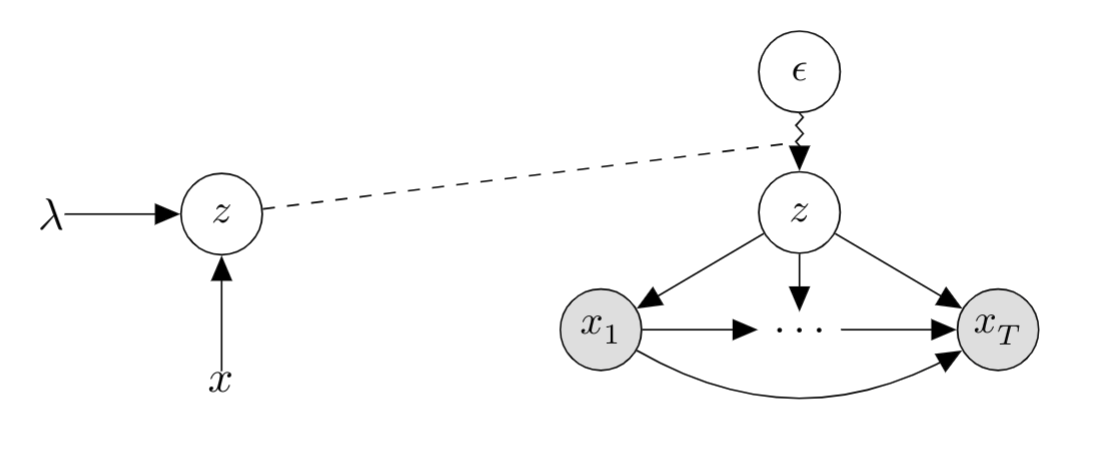

Deep Latent Variable Models of Natural Language

In this tutorial, Alexander Rush, Yoon Kim, and Sam Wiseman offered a rather dense coverage of a class of models which is becoming more and more widely used in NLP. Latent variable models have been around for a long time in statistical modelling (see: Factor analysis, LISREL, etc.). A latent variable is one which is not directly observed but which is assumed to affect observed variables. Latent variable models therefore attempt to model the underlying structure of the observed variables, offering an explanation of the dependencies between observed variables which are then seen as conditionally independent, given the latent variable(s).

The tutorial starts by introducing the types of latent variable models (discrete, continuous, and structured), their connection to deep learning models, and example NLP applications. It then proceeds to explain ELBO, the learning objective commonly used for such models. Inference strategies (exact, sampling, and conjugacy) are then examined before they delve into more advanced topics such as the Gumbel-Softmax. Finally, three recent deep latent variable NLP models and the tricks used to make them work are treated. Overall, this is a great resource for a direction of research that is certain to grow:

https://nlp.seas.harvard.edu/latent-nlp-tutorial.html

CONLL 2018

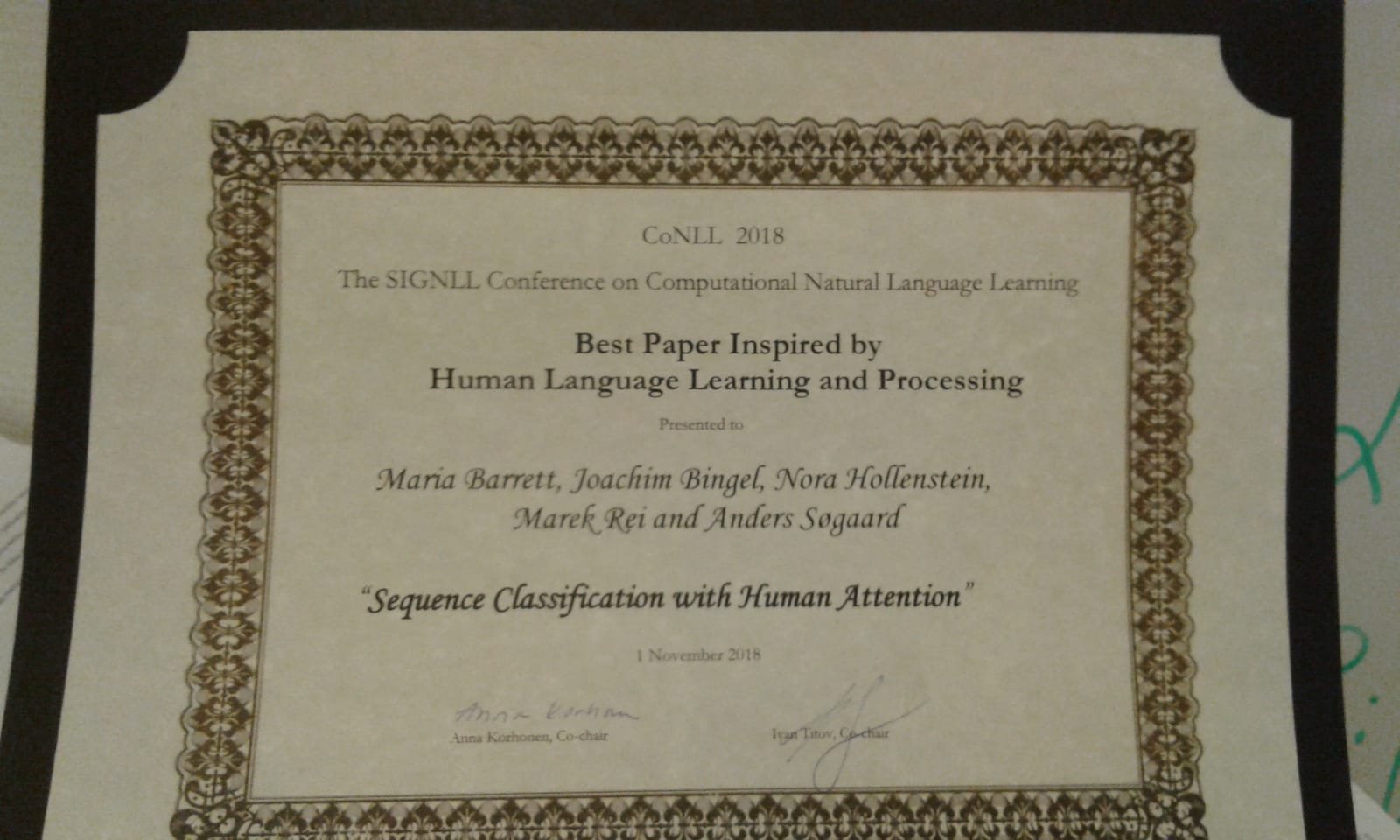

Sequence Classification with Human Attention

Full disclosure: this paper comes from our own group, so we might be a little biased here. Speaking of which, a recent theme in the field has been the call for more inductive bias and ways to introduce it. In this paper, the authors connect dots from previous work in our group by combining techniques known from multi-task learning with signals of human language processing. In particular, they use a bidirectional RNN with attention for sequence classification. So far so good, but the interesting part is that the network’s attention mechanism is enticed to more closely model human attention as attested by gaze patterns recorded in eye-tracking experiments. This is achieved through an auxiliary loss which, notably, can be minimized from external gaze data, such that no eye-tracking recordings are needed at test time. The paper shows that across three sentence classification tasks, biasing the machine attention towards human attention leads to consistent performance gains and results in sensible attention patterns that both validate the approach and help analyzing system decisions.

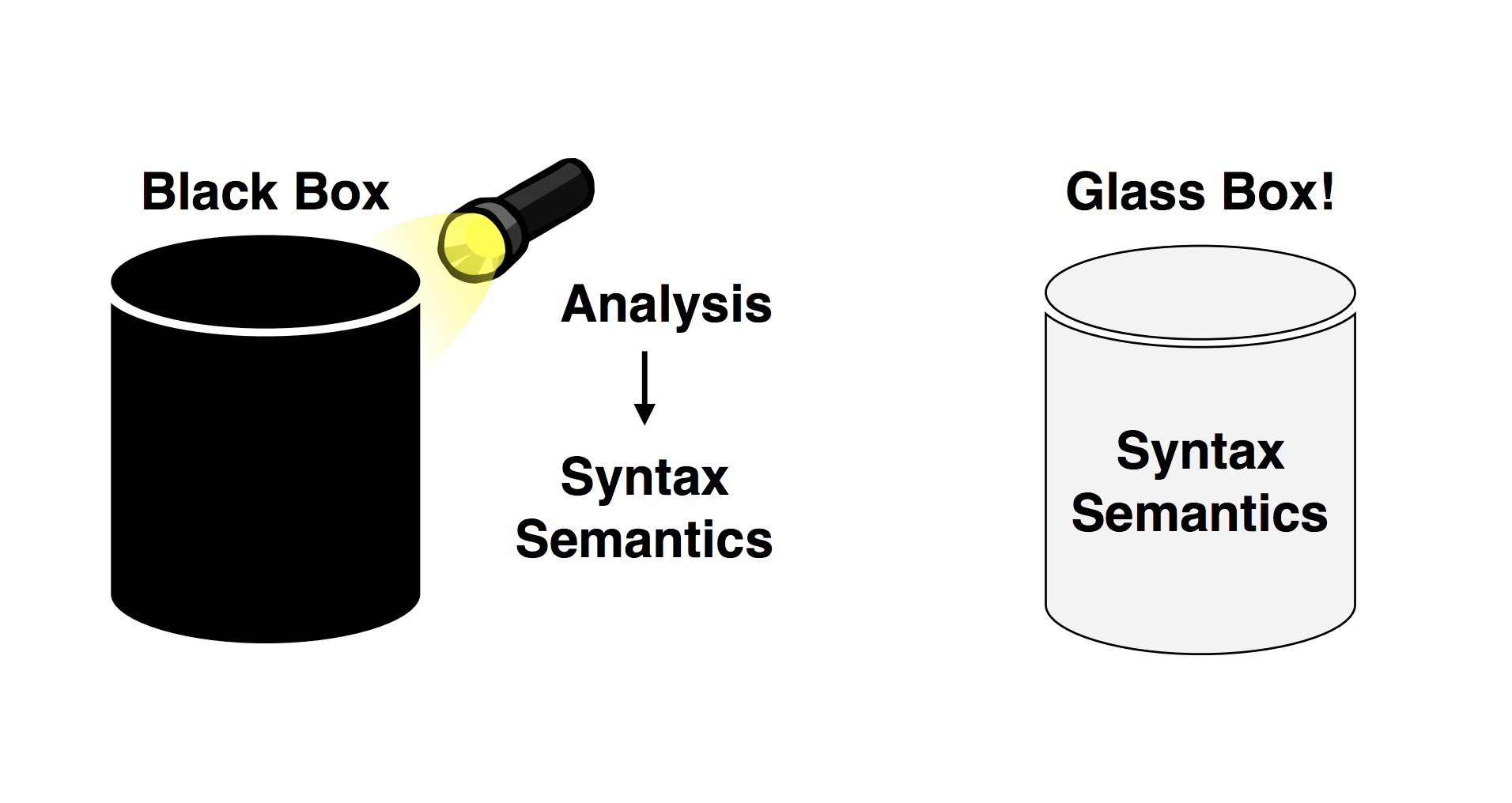

Staring Into the Darkness

Blackbox NLP was one of the most highly anticipated workshops at the conference (not just for me, apparently, 700 registrants!) and it delivered on its promise. The workshop dealt with the problem of interpretability in neural network models: how can we know what is encoded in representations learned by our models? What are they capable of learning and what are they not capable of learning? Inspired by previous work on representation analysis and on examining the linguistic generalisation learned by neural models, the workshop offered a way forward for dealing with a problem which has long been seen as an elephant in the proverbial NLP room.

It kicked off with a talk by Yoav Goldberg which stressed the importance of the recent trend of work which treats NLP models/representations as “Organisms” and constructs hypothesis which are then tested empirically - an approach which is uncommon in computer science. He then described ongoing work on testing the expressive and computational capabilities of and extracting discrete representations from RNNs: http://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/weiss18a.html, https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.09357, https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.04908.

Slides: http://u.cs.biu.ac.il/~yogo/blackbox2018.pdf

In the next talk, it was Graham Neubig’s turn to make the case for incorporating linguistic structure in neural models through latent variable modelling (sound familiar? See the first section in this blog!). Specifically, in the talk Graham describes three recent models:

-

Multi-space Variational Encoder-Decoder for labeled sequence transduction with semi-supervised learning which models the meaning of a word (a complex, high-level concept) as a continuous variable (using the reparametrization trick) and the closed-class and interpretable morphological features as discrete variables (using the Gumbel-Softmax). The model performs supervised learning by maximizing the variational lower bound on the marginal log likelihood of the data and annotated labels. For unlabeled data, an autoencoding objective is used to construct a word conditioned on its lemma and the set of discrete latent variables (a proxy for the morphological labels) which is associated with a it.

-

StructVAE which again performs semi-supervised learning (with structured latent variables) by employing an off-the-shelf semantic parser to parse natural language into latent meaning representations and a decoder to reconstruct the meaning representations into natural language. This allows both supervised training of the inference model on parallel Natural Language-Meaning representation data, and unsupervised training on natural language alone by maximizing the variational lower bound of the likelihood using REINFORCE.

-

Unsupervised Learning of Syntactic Structure with Invertible Neural Projections which uses invertible neural projection (super nifty, ha?) to enable the learning of word embeddings which are conditioned on the latent syntactic representation (e.g. dependency parse) in an unsupervised setting. The usefulness of this is demonstrated for both Unsupervised POS tagging (which is modelled with a markov prior) and unsupervised dependency parsing (DMV).

Slides: http://www.phontron.com/slides/neubig18blackbox.pdf

Finally it was Leila Wehbe’s turn to awe the predominantly NLP-oriented audience with a fresh perspective from the intersection of machine learning and cognitive science. She presented very exciting work about how the representations from NLP’s various artificial neural network models can be used to analyse complex brain activity (MEG and fMRI) data. Among the findings she presented it was:

-

MEG activity (MEG can resolve events with a precision of 10 milliseconds or faster) is well predicted by word embeddings, but poorly predicted by (universal) sentence encoders.

-

For fMRI data (which has a latency of several hundred milliseconds), both word embeddings and sentence encoders can be predictive of brain activity. Here is the catch, though: they predict different regions of the brain! Put very roughly, word embeddings are more predictive of regions associated with initial semantic processing, while sentence encoders (which include context + current word or just context) better predict regions associated with later semantic processing and composition.

The talk concludes on a speculative note and with a reference to something I’ve been running into a lot lately, David Marr’s levels of analysis, which we’ll link to but not further discuss in this blog. Food for thought.

Other Workshop Highlights:

* Interpretable Structure Induction Via Sparse Attention: Can dynamic sparse, regularized, constrained and structured tells our models to attend to produce a decision?

* Understanding Convolutional Neural Networks for Text Classification: What does each filter capture? Which n-grams contribute to the classification?

* Extracting Syntactic Trees from Transformer Encoder Self-Attentions: Self-attention weights from MT systems are extracted to build trees? Where is the attention mostly directed? Does it resemble trees from linguistic theories?

* And the best paper: Under the Hood: Using Diagnostic Classifiers to Investigate and Improve how Language Models Track Agreement Information: Using diagnostic classifiers to both understand and improve neural models.

Main Conference: Day One Highlights

Cross-lingual Knowledge Graph Alignment via Graph Convolutional Networks

This paper proposes a new approach to KB alignment using graph convolutional networks (GCN). They leverage entity embeddings learned by the GCNs, using both relational and the attributional triples in KGs to learn entity alignments. Their approach shows good improvements over previous methods and seems like a step in the right direction.

Neural cross-lingual named entity recognition with minimal resources

This paper attempts to tackle NER in an unsupervised transfer setting. The assumption is that there is labelled data in the source language, monolingual corpora in both source and target languages and a small dictionary of words between the. They use English (source language) to learn NER and try to transfer it to Spanish, German and Dutch (target languages). The method is as follows: First, they train monolingual word embeddings and project them into a shared space using the dictionary words as anchor points. This alignment is refined iteratively by inducing new/better dictionaries using source and target words which are very close to each other in the shared space. They then translate source language’s dataset by treating each word’s nearest neighbor as its translation and train an NER on this translated dataset. The model used is a hierarchical Bi-LSTM with self-attention and CRF.

Learning to split and refrom Wikipedia edit history

This paper releases a new dataset for text simplification called WikiSplit which contains one million data points in English. The approach taken to create the dataset is to look at adjacent versions of Wikipedia articles and identify candidate pairs using tri-gram affixes. These are then filtered for sentence similarity using BLEU. This dataset has about 33.1 million running tokens compared to 344k tokens of WebSplit, which was previously the biggest such dataset. They use a one-layer LSTM with attention and copying and train it both on WebSplit and WikiSplit. They observe a ~30 point increase in BLEU when the model is trained on WikiSplit. The the datasets are combined, the increase in BLEU is ~32 points.

Textual Analogy Parsing: What’s Shared and What’s Compared among Analogous Facts

This paper focuses on a particular discourse phenomenon, textual analogy, which the authors define as a higher-order semantic relation that captures the points of similarity and difference between semantic role structures. They define the new task of Textual Analogy Parsing (TAP), the goal of which is to extract analogy frames from text. They release a new dataset of expert-annotated quantitative TAP frames from the WSJ corpus, and show that once extracted, quantitative TAP frames can be visualized as plots. Thus, TAP forms the basis for the new application of automatically plotting quantitative text. Their best model combines ideas from recent neural approaches to SRL and co-ref, but interestingly benefits a lot from using integer linear programs (ILPs) to decode into structured outputs. Using thorough error analysis, authors suggest that there is still room for improvement on the TAP task.

SWAG (Situations With Adversarial Generations)

This paper introduces another Natural Language Inference dataset, with the stated goal of “unifying natural language inference and commonsense reasoning”. The dataset consists of 113k multiple choice questions which are extracted from video captions and therefore grounded to real-life scenarios. A language model is used to extract a large number of negative examples (hypotheses) for each premise. To deal with the annotation biases which have been found in many of the currently used NLI datasets, the authors employ a dataset construction procedure which they call Aderserial Filtering. In AF, an ensemble of stylistic classifiers is iteratively trained and then used to reduce stylistic artifacts by filtering out examples which are easy to classify based on stylistic features and replacing them with more difficult “adversarial” ones. The authors report that human performance on this dataset at an accuracy of 88% while the SOA NLI models are below 60%. Exciting stuff - until Rowan reveals that BERT (released roughly two weeks after SWAG) is already at 86%. At this point, even Rowan’s enthusiastic presentation can’t keep the audience from wondering about how a new benchmark which was meant to be difficult had been overfit so quickly.

Deterministic Non-autoregressive Neural Sequence Modelling by iterative refinement

Can we get rid of the autoregressive bottleneck in Machine Translation and other sequence modelling tasks without hurting performance too much? It seems so. This work builds on work by Gu et. al and others, proposing a model where the dependencies between target symbols is modelled using intermediate latent variables and an iterative refinement scheme where each iteration can be seen as denoising a corrupted output sequence. Decoding can now be parallelised!

Contextual Parameter Generation for Universal Machine Translation

This paper endows standard Neural Machine Translation models with a Contextual Parameter Generator (CPG) which facilitates efficient translation between multiple languages. While training on multiple source and target languages with a traditional encoder-decoder architecture, the CPG is used to generate the encoder and decoder’s parameters for a given language pair, conditioned on language embeddings which the model learns for every language. They show that this method requires a significantly lower number of parameters for a given number of training examples because of the sharing of structure between languages. FInally, they also demonstrate that the learned language embeddings reflect agreed upon ideas about how related certain languages are to each other.

TRANX: A transition-based neural abstract syntax parser for semantic parsing and code generation

This paper applies semantic parsing in the domain of source code. The framework is applied to parse natural language (NL) into python and SQL (target domains). The output of this framework is an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) which is then used to generate the actual program. For converting NL into AST, the ASDL grammar of each target domain is used to condition a transition system which generates an AST as a sequence of tree-constructing actions. A standard Bi-LSTM encodes the NL sentence. The decoder is a pointer network which decides whether to copy or generate a token depending on previous actions and parent types. To evaluate their approach, the authors use GEO & ATIS datasets for generating λ-calculus logical forms, and Python Django & WikiSQL for domain specific code generation tasks.

Other Day One Highlights:

* Towards Dynamic Computation Graphs via Sparse Latent Structure

* Targeted syntactic evaluations of language models

* Unsupervised learning of syntactic structure with invertible neural projections

* Rational Recurrences

* Efficient Contextualized Representation: Language Model Pruning for Sequence Labeling

Main Conference: Day Two Highlights

XNLI

Cross-lingual transfer of NLI models can now be evaluated across 15 languages! BERT already has results, of course: https://github.com/google-research/bert/blob/master/multilingual.md

Gromov-Wasserstein Alignment of Word Embedding Spaces

One of the many, many word embeddings alignment papers at the conference. This one caught our attention with a novel view of the task as a problem of relational optimal transport. They use a generalization of optimal transport which is based on Gromov-Wasserstein distance. This basically means that we now operate directly on the distances between pairs of points (words) rather than the points themselves, i.e. the goal becomes to minimize the difference in similarity between Word A and Word B for all word pairs (in two or more word embeddings spaces). Cool stuff!

Semi-supervised Sequence Modeling with Cross-view Training

Another blast from the not-so-distant past (think multi-view training, co-training, co-em, etc.). This paper proposes a simple but effective semi-supervised learning algorithm which combines supervised training with self-training on unlabelled examples where a teacher with a full-view of the input is used to label an example, then a number of students with “partial-views” (e.g only the hidden states from the timesteps before or after word for a bi-lstm sequence tagget) of the input are trained to minimize the KL-divergence with the teacher’s label. The authors test this on a large set/combination of tasks and demonstrate that this approach can easily be combined with elaborate multi-task settings.

Recurrent Neural Networks in Linguistic Theory: Revisiting Pinker and Prince (1988) and the Past Tense Debate

Christo Kirov presents work from a TACL paper which re-examines the work of Rumelhart and McClelland on the transduction of English verbs from their stem. Rumelhart and McClelland’s early model was subsequently heavily criticised by Pinker and Prince for its poor performance and lack of ability to generalise or demonstrate learning patterns that are similar to those of humans (without the manipulation of the input distribution). In this study, the authors conduct a set of experiments showing that the majority of Pinker and Prince criticisms of Rumelhart and McClelland’s model do not apply to current Encoder-Decoder Neural models when used for the same task of inflection. Kirov and Cotterell conclude that a) our neural models have become much better at this task, b) even though current neural models may not reflect human learning patterns, they can still be useful as modelling tools.

Other Day Two Highlights:

* Joint Multilingual Supervision for Cross-lingual Entity Linking

* Imitation Learning for Neural Morphological String Transduction

* Investigating Capsule Networks with Dynamic Routing for Text Classification

* QuAC : Question Answering in Context

* Policy Shaping and Generalized Update Equations for Semantic Parsing from Denotations

Main Conference: Final Day Highlights

Pathologies of Neural Models Make Interpretations Difficult

This paper takes a closer look at the methods used to interpret neural model predictions through input perturbation or the gradient with respect to a given feature. They devise an input reduction technique (for tasks like question answering and NLI) where the least important words from a given input sentence are iteratively removed while the model’s prediction remains the same. They find that with sentences reduced to as little as one word, models can paradoxically still make high confidence predictions. Furthermore, given these same reduced inputs, humans do not find them reasonable and can not use them to make correct predictions. The authors offer two explanations for the models’ anomalous behavior which are based on the idea of model overconfidence: a) When trained with a maximum likelihood objective, neural models’ confidence provides a poor estimate of prediction uncertainty; b) the model’s importance assignments (i.e. the interpretation) to input words shift dramatically with the removal of the least important words. Finally, they propose a solution which involves regularising the models by maximising their entropy on reduced inputs showing that it can mitigate model overconfidence.

Syntactic Scaffolds for Semantic Structures

One of the main trends of the conference was the incorportation of linguistic information — particularly syntax — into models trained on semantic tasks. This was one of the coolest papers in that direction. The authors refer to their approach as “syntactic scaffolding”, wherein they employ a multi-task objective for steering a model towards learning some semblance of syntactic structure alongside the semantically-oriented task-at-hand (Semantic Role Labeling). The cool thing here is that they take advantage of the fact that SRL-labeled token spans are typically syntactic constituents in-and-of themselves and can represented as such via a shallow label-set (thus foregoing the need for a full syntactic parse). The tasks they employ in this case are constituent identity (is a span a constituent or not?), non-terminal labeling (the category of the span itself), non-terminal+parent labeling (the span’s category plus the category of its immediate ancestor), and labeling common non-terminals (whether a span belongs to NP/PP, other categories, or has a NULL label). Ultimately, they train a Semi-Markov Conditional Random Field on three tasks: Frame SRL, PropBank SRL, and Coreference Resolution (CONLL 2012). Though their single-task baseline alone outperforms prior approaches, they report further state-of-the art performance on all tasks when jointly-training with all four syntactic scaffolding sub-tasks.

What Makes Reading Comprehension Questions Easier?

In a time when new QA datasets are released seemingly daily, this paper offers a nice insight into the way such datasets are implicity constructed. In a qualitative comparison of 12 popular QA datasets, Sugawara, et al. propose two heuristics for dividing questions into easy and hard subsets. One such heuristic is to simply provide the first k tokens of a question to a baseline system (e.g. with k = 4, will I quality for OSAP if I’m new in Canada -> will I quality for). The second heuristic is simply the unigram overlap between questions and sentences in the context. Surprisingly, the authors’ baselines perform well on some datasets even when incorporating such naive heuristics! With this in mind, a question is deemed hard when its answer is not found in the most similar context sentence or when employing k = 2 tokens; any other question is deemed easy. Following this division, the authors perform an exensive analysis, wherein they group hard questions by their overall validity (is the question unsolvable or ambiguous?), reasoning skill (does the solution require simple word matching, paraphrasing, or mathematical/logical reasoning?) and multiple-sentence reasoning (does the solution rely on coreference, causal relations, etc.?). As expected, the baselines systems floundered when tasked with learning/solving such complex phenomena across many datasets. Overall, we found this work very important in the sense that it investigated how imbalanced some QA datasets can be, and how, as a result, systems performing well on them should not be assumed to understand language uncritically.

Other Final Day Highlights:

* Phrase-level Self-Attention Networks for Universal Sentence Encoding

* A Nil-Aware Answer Extraction Framework for Question Answering

* The Importance of Being Recurrent for Modeling Hierarchical Structure

Trends:

1. What is wrong with our datasets and models?

- How Much Reading Does Reading Comprehension Require? A Critical Investigation of Popular Benchmarks. (Best short paper)

- What Makes Reading Comprehension Questions Easier?

- Pathologies of Neural Models Make Interpretations Difficult

2. Incorporating linguistic knowledge into neural models

- Linguistically-Informed Self-Attention for Semantic Role Labeling.(Best long paper)

- Phrase-level Self-Attention Networks for Universal Sentence Encoding

- Syntactic Scaffolds for Semantic Structures

3. Interpreting and understanding neural models

- BlackboxNLP

- Targeted syntactic evaluations of language models

- The Importance of Being Recurrent for Modeling Hierarchical Structure

- Rational Recurrences

4. Latent Variable Models

- Unsupervised learning of syntactic structure with invertible neural projections

- StructVAE

- Deterministic Non-autoregressive Neural Sequence Modelling by iterative refinement

Back to the Future

In his keynote talk, Johan Bos spoke of Meaning and Meaning representations. Do our natural language understanding models understand? Do the tasks we use to test our models (NLI,QA, etc.) actually require understanding? He presented The Parallel Meaning Bank, a corpus of parallel sentences in four languages annotated syntactic analysis, word senses, thematic roles, reference resolution, and formal meaning representations (DRT). He argued for the use of use language-neutral meaning representations to draw inferences for tasks like machine translation. A compelling argument, since the actual objective of translation is to capture the meaning of a source language sentence rather then the n-gram overlap with a reference translation. Will this actually be the direction in which we will be heading? I’m not so sure. But if you’re interested, the following shared task might be for you: https://competitions.codalab.org/competitions/20220